V‑JEPA 2 and the Rise of World Models: A Practical Guide for Robotics and Agents

If you follow modern AI for robotics and agents, you’ve probably noticed the phrase “world model” popping up everywhere. In 2025, Meta’s V‑JEPA 2 made that trend impossible to ignore: a self-supervised video world model trained on over a million hours of internet video, then adapted to control real robots zero-shot in new labs using only ~62 hours of unlabeled robot footage. arXiv

This post breaks down:

- What world models and JEPA actually are

- How Meta’s V‑JEPA 2 uses a world model to control robots

- Why this matters for your own agents and robotics stack

- Concrete steps and resources to start experimenting yourself

1. Quick refresher: what is a “world model”?

A world model is an internal simulator of the environment learned from data. Instead of directly mapping observations → actions, you first learn a model that predicts:

- How the world will evolve (future observations / latent states)

- What rewards or outcomes will result from actions

Then you plan or learn policies inside that model instead of always interacting with the real environment.

A classic example is the World Models paper by David Ha and Jürgen Schmidhuber. They split an agent into:

- Vision (V): a VAE that compresses raw image frames into a latent vector

- Memory/Model (M): an MDN‑RNN that predicts the next latent vector given actions

- Controller (C): a tiny controller that picks actions based on these latent states

Trained this way, their agent solved the CarRacing‑v0 environment from raw pixels and performed strongly on VizDoom, effectively learning and then acting inside its own learned “dream world.” ar5iv+1

Modern work like DreamerV3 pushes this further: it learns a compact world model that predicts future latent states and rewards, then trains an actor‑critic purely from imagined trajectories. This single configuration masters over 150 tasks (including the “collect diamonds in Minecraft from scratch” challenge) with fixed hyperparameters. Danijar+1

Key intuition:

A world model lets your agent think ahead, try strategies in “simulation,” and learn more efficiently than purely model‑free RL.

2. What is JEPA in plain English?

JEPA stands for Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture, introduced by Yann LeCun and colleagues as a core building block for more human‑like AI. The idea appears in I‑JEPA, a self‑supervised image model. arXiv

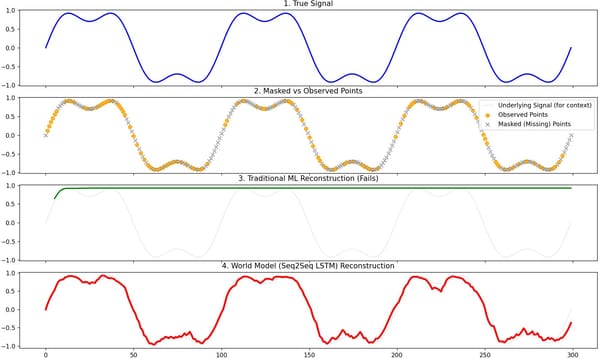

Instead of reconstructing pixels, JEPA does something smarter:

- Take a context region of an image (or video).

- Encode it into a latent embedding.

- Predict the embeddings of masked target regions of the same image/video.

So the model never tries to generate pixels. It only learns to match abstract representations:

- It focuses on semantics (objects, layout, motion patterns), not low‑level texture.

- It avoids representation collapse by using separate context and target encoders with EMA and a predictive head. Medium+1

- It scales well with Vision Transformers and large datasets, achieving strong performance on downstream tasks without hand‑crafted augmentations. arXiv

This architecture—predicting embeddings instead of pixels—is crucial when you move from passive perception to active agents. It’s exactly what V‑JEPA 2 leverages.

3. Case study: V‑JEPA 2 as a video world model for robot control

In June 2025, Meta released the paper “V‑JEPA 2: Self‑Supervised Video Models Enable Understanding, Prediction and Planning.” arXiv

At a high level, here’s what they did:

- Pretrain a massive JEPA on video

- Train an action‑free JEPA video model (V‑JEPA 2) on >1M hours of internet video plus images.

- Objective: predict representations of future video patches from context, not pixels.

- Demonstrate strong video understanding

- Achieves strong performance on motion understanding benchmarks like Something‑Something v2 and state‑of‑the‑art results on human action anticipation (e.g., Epic‑Kitchens‑100). arXiv

- After aligning with a large language model, V‑JEPA 2 delivers leading performance on video QA tasks such as PerceptionTest and TempCompass. arXiv

- Turn it into an action‑conditioned world model (V‑JEPA 2‑AC)

- Post‑train the pretrained video model using <62 hours of unlabeled robot videos from the Droid dataset.

- This adds action conditioning in latent space, effectively converting a passive video model into a world model that can predict how scenes evolve under robot actions. arXiv

- Deploy on real robots, zero-shot

- Deploy V‑JEPA 2‑AC to control Franka arm robots in two different labs.

- Use the model to plan in latent space to reach visual goal images (e.g., picking and placing objects).

- Crucially:

- No data collected from robots in those target labs

- No task‑specific training or reward functions

- The model was pre‑trained on web video and a small, generic robot dataset, then successfully deployed in new environments with different backgrounds and setups. arXiv

In other words, V‑JEPA 2 is a world model trained mostly from passive internet video, then lightly adapted to become a planning model for real robots.

For people building robots and agents, this is a big deal: it demonstrates that video world models + JEPA can bridge the gap between web‑scale learning and real‑world control.

4. Why world models + JEPA are a powerful combination

Let’s unpack why V‑JEPA 2 is interesting beyond the benchmarks.

4.1 Data efficiency and transfer

- The core JEPA model learns from unlabeled video at internet scale.

- Only a small amount (~62 hours) of unlabeled robot footage is needed to adapt it into V‑JEPA 2‑AC for control. arXiv

Instead of collecting huge task‑specific datasets (e.g., thousands of labeled pick‑and‑place demos per lab), you:

- Pretrain a generic video world model.

- Do light, domain‑specific adaptation.

- Use planning to generalize to new tasks and environments.

4.2 Semantic, predictive latent space

JEPA’s “predict embeddings, not pixels” design means:

- The model focuses on objects, motion, and physical interactions, which are exactly what you need for control. arXiv+1

- The latent space is stable and expressive enough to support long‑horizon prediction and planning.

- Compared to autoregressive pixel prediction, this is more efficient and better aligned with what downstream planners care about.

4.3 Planning in imagination

Just like DreamerV3 uses its world model to imagine trajectories, V‑JEPA 2‑AC allows planning directly in latent space:

- Sample candidate action sequences.

- Roll them forward inside the world model.

- Score them against a goal image or cost function.

- Execute the best one on the robot. arXiv+1

This closes the loop from self‑supervised video understanding → predictive world model → action planning.

5. How this changes the robotics & agent stack

For robotics startups and applied ML teams, world models + JEPA reshuffle the architecture of your stack.

Instead of:

Policy = f(observation) → action

you move to:

World model = g(history, action) → future latent, reward

Policy / planner = h(world model, goal) → action

This unlocks several advantages, echoed by both research and industry analysis: Andreessen Horowitz+1

- Sample efficiency: Learn policies through imagination instead of expensive real‑world rollouts.

- Off‑policy reuse: You can replay and re‑simulate past data under new candidate policies.

- Neural simulation: Use world models as neural simulators to generate synthetic data, explore edge cases, and test safety.

- Cross‑domain transfer: Pretrain once on generic video; adapt to new embodiments and environments with small amounts of interaction data.

The V‑JEPA 2 result shows that this isn’t just theory: a JEPA‑based video world model can plan for real robots in unseen labs.

6. Blueprint: building your own JEPA‑style world model

You don’t need Meta’s compute budget to start. Here’s a pragmatic blueprint you can adapt.

Step 1 – Decide your domain and embodiment

- Simulated agents (e.g., game, gridworld, custom sim)

- Real robots (arm, mobile base, drone)

- Software agents (UI automation, web navigation)

This determines your observation modality (images, video, proprioception, text) and action space.

Step 2 – Collect passive video and logs

- For robots: record unscripted teleop or random exploration videos + actions.

- For agents: record screens, UI states, and action traces.

- Start small: tens of hours go a long way when combined with self‑supervision.

Step 3 – Pretrain a JEPA‑style encoder

You don’t have to start from scratch:

- Use open‑source I‑JEPA / JEPA implementations (e.g., community PyTorch repos and experiments that implement the I‑JEPA paper). GitHub+1

- Or adapt general SSL frameworks (BYOL, DINO, etc.) to a JEPA‑like objective:

- Mask target regions.

- Predict target embeddings from context embeddings.

- Use EMA target encoder and prediction head to avoid collapse.

Goal: learn a semantic latent space for your observations.

Step 4 – Make it action‑conditioned (turn it into a world model)

Like V‑JEPA 2‑AC, you then add action conditioning:

- Model:

- zt=encoder(ot)z_t = \text{encoder}(o_t)zt=encoder(ot)

- Predict zt+1z_{t+1}zt+1 and (optionally) reward rtr_trt given zt,atz_t, a_tzt,at.

- Training objectives:

- Latent prediction loss (e.g., cosine distance in embedding space).

- Optional reward or value prediction loss if you have reward signals.

You now have a world model: given current latent and an action, it predicts what the world will look like next.

Step 5 – Plan or learn a policy inside the world model

You have two main options:

- Planning / MPC

- Sample candidate action sequences.

- Roll them forward in the world model for N steps.

- Score against a goal image / latent / cost.

- Execute the best first action on the real system.

- Model‑based RL like DreamerV3

- Use imagined trajectories from the world model to train an actor‑critic in latent space. GitHub+1

- Periodically refresh the world model with new real data.

For early experiments, goal‑image planning is often simpler and more interpretable.

7. When should you reach for a world model?

World models and JEPA aren’t always necessary. They shine when:

- Rewards are sparse (e.g., long‑horizon tasks like assembly, logistics, open‑world games).

- Data collection is expensive or risky (robots, self‑driving, hardware‑in‑the‑loop control).

- You need zero‑shot or few‑shot transfer to new environments.

- You care about simulated what‑if analysis (safety, debugging, synthetic data generation).

For short‑horizon, fully supervised tasks (classification, simple grasping with dense labels), a plain supervised model may still be simpler.

8. How to start experimenting (today)

Here’s a concrete starter path you or your team could follow:

- Read the core papers & posts

- Reproduce a baseline world model

- Run an open‑source World Models or DreamerV3 implementation on a small benchmark.

- Get comfortable with the training loop, logging, and rollouts.

- Train a small JEPA encoder on your own data

- Use a JEPA tutorial or minimal implementation to pretrain encoders on your domain video. Medium+1

- Visualize latent clusters, linear probes, or simple downstream tasks.

- Add action conditioning & simple planning

- Train a latent dynamics model on your system logs.

- Implement a basic CEM or random shooting planner in latent space for a simple goal.

- Iterate toward your product use case

- Introduce more realistic scenes, multi‑task objectives, or language‑conditioned goals.

- Use the world model as a neural simulator to generate synthetic data for edge cases, as highlighted in industry discussions about world models and “neural simulators.” Andreessen Horowitz

9. Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

1. Treating the world model as a black box

If you never inspect latents, rollouts, or reconstruction quality, debugging is painful.

→ Regularly visualize imagined futures and compare them to real data.

2. Overfitting to a single environment

If you only train on one lab or sim, your model will often fail catastrophically elsewhere.

→ Mix multiple scenes, textures, lighting conditions; use randomization where possible.

3. Ignoring temporal credit assignment

Short context windows limit long‑horizon reasoning.

→ Make sure your architecture has sufficient temporal receptive field (via sequence models or memory).

4. Underestimating evaluation complexity

It’s easy to get slick demo videos that don’t generalize.

→ Evaluate on held‑out environments and out‑of‑distribution goals, like V‑JEPA 2’s deployment in unseen labs. arXiv+1

10. FAQ

Q: Is a JEPA‑style world model only useful for robotics?

No. Any domain with sequential observations—games, autonomous driving, UI automation, simulation, even video‑based analytics—can benefit from world models and JEPA‑like objectives.

Q: Do I need millions of hours of data like V‑JEPA 2?

No. The Meta result shows the extreme end of scaling. In practice, you can get value from tens to hundreds of hours of domain‑specific video, especially if you reuse existing pretrained encoders.

Q: How is JEPA different from diffusion or autoregressive video models?

Diffusion/autoregressive models focus on high‑fidelity pixel generation and are often expensive at inference. JEPA learns a predictive latent space that is cheaper to roll out and more directly aligned with control and planning. Andreessen Horowitz+1

Q: Can I combine language models with world models?

Yes—V‑JEPA 2 shows that aligning a video world model with an LLM enables strong performance on video question‑answering benchmarks. arXiv In practice, this means you can condition planning on natural language goals and explanations.

Closing thoughts for activemodels.ai

The V‑JEPA 2 work is one of the clearest public demonstrations that JEPA‑style video world models can power real robot control in unseen environments, not just benchmark scores.

If you’re building agents or robots, now is the time to treat world models as a first‑class part of your stack—not a toy research idea. Start small, iterate in your domain, and use the growing JEPA and world‑model ecosystem as your springboard.